In the spring of 2005, I attended my first event in the Society of Creative Anachronism (SCA), an Ithra session of classes. I was nervous, excited, and absolutely convinced that I could not set foot at an event without a hat on my head. And so I made a hat, which I loved. It was the first garment I constructed on my own. Later that spring, I came to an important realization while attending my second event, Glymm Mere’s Mayfair, a revelation that would influence my entire SCA experience. What a fourteenth century English woman really needs is a veil…

…and the rest is history.

“Images of frilled veils are extensive and span from the middle of the thirteenth century until well into the fifteenth century (Newton & Giza, 1983). These veils start out with soft edges and with each passing decade become increasingly more elaborate in presentation and more numerous in layers.

Known by many names, (frilled, ruffled, crimped, goffered, kruseler, fluted, wrinkled, fretworked) veils are depicted in artwork, the stained glass windows of churches, stone statuary, and even woven tapestries. However, it is the burial tomb effigies and brass etchings, in their abundance, that offer the best look at the unique women’s head coverings of the late fourteenth century.

Catherine de Beauchamp’s Fretwork Veil

© Moriarty

I have long been drawn to the exquisite burial tomb of Catherine de Beauchamp. She wears a detailed and complex fretwork veil that is a thing of beauty. Born in 1314, Catherine Mortimer was buried as a Countess along-side her husband Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick after their deaths in 1369. Her effigy wears a spectacular headdress which consists of two veils. A simple (likely woven) frilled veil sits over the top of an elaborate 12-layer fretwork veil (Sturtewagen, 2006/2007). The fretwork extends to the back of the veil, as well.

Avena Foljambe

© Margaret Scott

While researching my previous veil projects, I developed a fascination with the idea of creating a fretwork veil. Catherine de Beauchamp’s veil became my inspiration. Avena Foljambe’s effigy headdress, described by Margaret Scott (1986) as a thick combination of fluted veils stylized into a fretwork, is another beautiful example of this medieval English style.

The veil, itself, is a rectangle long enough to be doubled. This allows sufficient length to fold it in half, sewing a seam in the center on the underside of the veil. My previous frilled veils were both semi-oval in shape, which was likely less common than a rectangular veil in the fourteenth century. For this reason, I was excited to try this new shape.

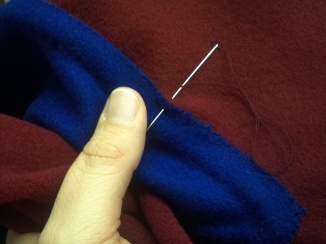

My early experiments indicated that it would be beneficial to slightly pleat the fretwork strips in order to increase the fullness of the fabric and allow the frets to open more easily when starched.

My initial plan was to fold the fretwork strips in half, with the crisp fold facing towards the front to provide a very neat appearance. However, upon examination of the pleating in the extant ruffs featured in Janet Arnold’s Patterns of fashion 4 (2008), it was clear that the linen had been hemmed on the front (outer) edge. Some of these ruffles were folded at the neckline, creating a multi-layer effect. As such, I decided to hem the outer edge of the fretwork veil strips, as well.

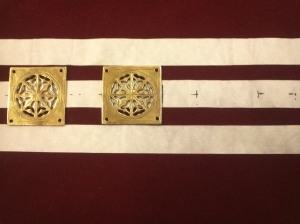

Pins for marking stitch placement.

Fretwork attached to veil.

A small portion of the starching sticks in place.

I conducted experiments in starching with both wheat and rice using the original sample fretwork piece that I had constructed. They provided some interesting results.

Due to the yellow/gold discoloration caused by utilizing wheat starch, I opted to starch the fretwork with a rice starch solution.

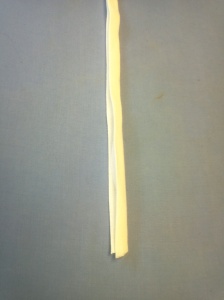

During my initial experiments in starching a fret strip, I tried pinning the frets open to dry after submerging them into the liquid starch. This process was difficult, did not result in crisp points on the frets, and basically starched small holes into the linen. For my next attempt at starching I made the decision to try using starching sticks. The idea was to fill the fret holes with something that would mold them into the proper shape while drying. Janet Arnold (2008) mentions the use of starching sticks and even displays two of them (reproductions) in Patterns of Fashion 4: The Cut and Construction of Linen Shirts, Smocks, Neckwear, Headwear and Accessories for Men and Women.

Completed Fretwork Veil

Photo by Gryphon Black

The completed fretwork veil at Kingdom Arts & Sciences.

Photo by Elisabeth Besancon

In the end, I was quite pleased with the results. 🙂

~ Cristiana

Arnold, J. (2008). Patterns of fashion 4: The cut and construction of linen shirts, smocks, neckwear, headwear and accessories for men and women. London: Pan Macmillan Ltd.

Newton, S. & Giza, M. (1983). Frilled edges. Textile History, 14 (2), 141-152.

Scott, M. (1986). A visual history of costume: The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. London, UK: B. T. Batsford Ltd.

Sturtewagen, I. (Winter 2006/2007). En kruset hoveddug: Catherine de Beauchamps hovedtØj.